Grass Padrique | The Fabulous Scientist

Before GPS and tablets, every strike and dip was inked by hand by geologists. It is a ritual of observation and artistry.

There is a certain romance in geology that isn’t always captured by equations, satellite images, or the neat layers of a GIS map. Long before digital mapping became the norm, geologists relied on their senses – eyes for linear structures, ears for running water, hands for the texture of minerals, and perhaps most overlooked of all, the slow, deliberate movement of ink across paper as they write their observations.

Before I started writing blog posts on this site, I carried a weathered field notebook in my bag to chronicle how my day went, lessons learned, and other geology-related stuff. The pages crackled softly under my fingertips, mixing with the smell of sun-warmed rock dust and the rhythm of quick notes taken beside an outcrop. Those notebooks carried the rawness of the field — hastily drawn contacts, corrected measurements, how the weather was that day, people I met, and most importantly, the food that I got to try that were often not available in the city.

These days, I still keep a special field notebook with me — the kind with sturdy, inviting pages perfect for slow observation. Although I only began using fountain pens in 2023, they’ve become part of a new ritual: sketching rocks, minerals, and textures with deliberate ink strokes. The glide of a nib on paper feels almost meditative, especially when capturing the bedding structure of a sedimentary rock, the geometry of a vein mineral as observed under the microscope, or the crisp edges of a crystal cluster in my collection. It’s a modern habit that echoes an older craft — a small way of honoring geological traditions in this digital age. My writing habit now is indeed heavily influenced by those days of writing my observations during geologic fieldworks using pencils and ballpoint pens. When I taught in UP-NIGS, my fellow educators and I encouraged our students to sketch with their pen and notebook to reinforce learning. I have included a few academic publications at the end of this blog that I encourage everyone to read about how writing reinforce learning.

The Quiet Ritual of Field Notebooks

Every field geologist knows that their notebook is more than a diary. It’s an extension of the mind. It is evidence. It is memory. One can just look at the sketches even months after and a geologist would remember vividly how that day went, the smell of the surroundings, the sound of nature.

Before digital cameras, we described an outcrop with words and few sketches. Before smartphone compasses, we wrote strike: 120°, dip: 35° SE with careful strokes, making sure the numbers wouldn’t wash away in the rain. The notebook was the field’s first “hard drive,” the place where discoveries lived long before they became maps, models, or chapters of a thesis.

Geologists often joke that you can tell a person’s sub-discipline by reading their notes:

- The structural geologist fills pages with arrows, planes, and tiny stereonets.

- The petrologist sketches minerals with soft shadows and near-symmetric precision.

- The volcanologist scribbles boldly, as if mirroring the energy of magma movements.

Every style unique, but all guided by the same principles: clarity, precision, and observation. For most, with a little artistry on the side.

Ink in the Field: Why Fountain Pens Mattered

Today, pencils dominate field kits for practicality, but historically, fountain pens had a quiet but important presence.

Their strength was in their expressiveness. A fountain pen line has personality — a natural variation in width and pressure that helps bring geological features to life. Perfect for:

- Sketching the curvature of folds

- Outlining igneous intrusions against a background of host rock

- Shading subtle lithologic boundaries

- Annotating hand sample diagrams

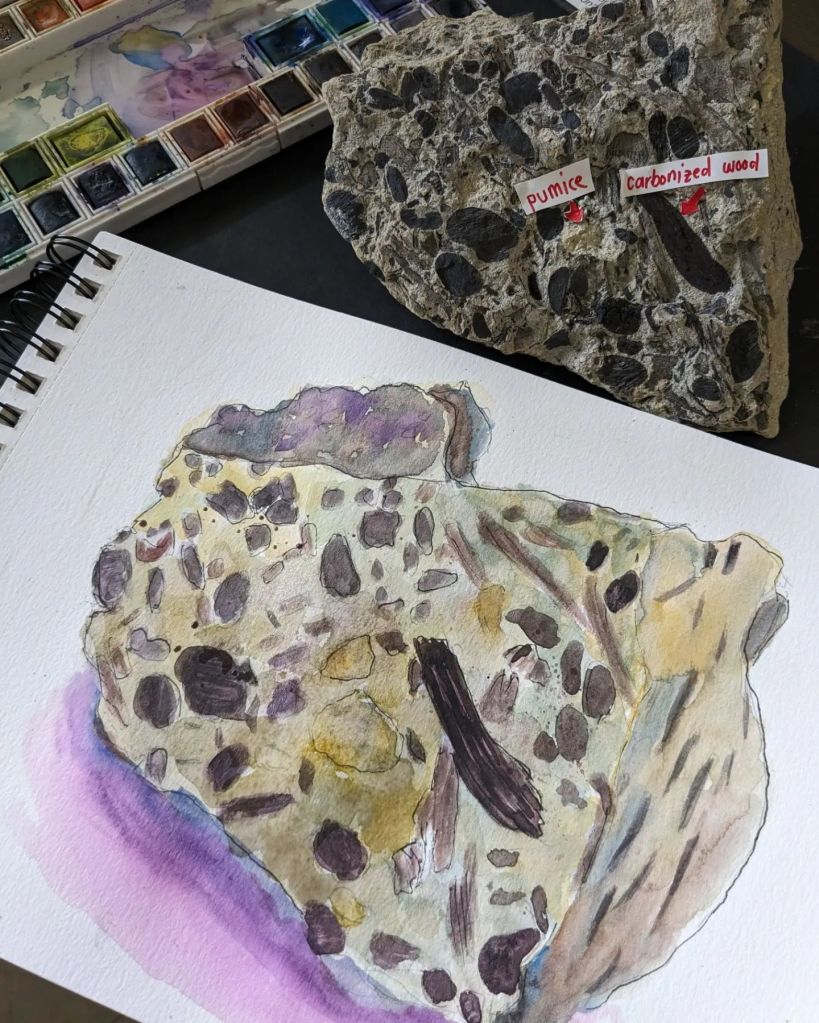

Below are some of the sketches I made using fountain pens and watercolors.

Ink also forces intention. You cannot erase it. Each stroke is a commitment, echoing the way geologists commit to an interpretation of a formation or contact zone.

For many geologists before the digital era, writing in ink carried a sense of ritual — an act of slowing down, observing deeper, and treating even the roughest field notes as a blend of science and craftsmanship.

When I sketch rocks now using my fountain pens on my Elias notebook or create ink-and-wash illustrations in my watercolor notebook, I feel connected to that same tradition. It’s no longer about necessity; it’s about presence and artistry.

Maps Before Tablets: When Everything Was Drawn by Hand

Before GIS, geological maps were a labor of love.

You spent long days under the sun gathering measurements, and longer nights tracing boundary lines, annotating structural symbols, and carefully adding colors to differentiate units.

Hand-drawn maps required:

- Patience

- Clean linework

- Smooth ink flow

- Consistent symbology

- A steady hand and a clear mind

Fountain pens were traditionally used for annotation, fault traces, and outlining map features, while watercolor added depth and subtle color gradients.

Many of these maps still survive in university archives — each one a beautiful hybrid of precision and artistry. In a way, they remind us that geological mapping once had the pace of an art studio: slow, quiet, meticulous.

Teaching the Next Generation: Passing Down the Craft

During my years as a Teaching Associate and Museum Research Associate, I had opportunities to reintroduce students to this tactile tradition although most of them did prefer ballpoint pens or gel pens. Many of them had never used a fountain pen, much less sketched a rock with one.

Yet during our sketching sessions, something beautiful happened:

- They slowed down.

- They looked closer.

- They began asking questions as I draw the cleavage planes, twinning planes, and other features of a rock.

Pen and ink have a way of anchoring the mind. They make geology personal again. When I sketch rocks with kids during painting sessions outdoors and even online, I see that same focus. Whether we’re drawing a fossil or painting a particular tree we spotted on campus, the act of drawing becomes a bridge between observation and memory.

Recreating the Tradition Today

If you’d like to emulate what an earth scientist do with their field notebook, here are a few simple ways you can do with your family or friends:

1. Sketch with a fountain pen.

Even a beginner pen brings expressive linework perfect for structure, texture, and mineral shapes. You’d be surprised at how different it feels to write with one compared too pencils or ballpens.

2. Map a small space.

Try your garden corner, a rock wall, or even your terrarium setups. Use traditional field symbols.

3. Keep a “daily geology” notebook.

Fill it with observations:

- Cloud formations

- Rock textures

- Soil colors

- Bird sightings

- Interesting patterns from walkabouts

4. Experiment with ink and watercolor.

Many classic field sketches were ink outlines with light washes — ideal for Elias or cotton watercolor paper.

Why This Tradition Still Matters

In today’s world of digital mapping, automated workflows, and machine learning, there is something grounding about returning to ink and paper.

Handwriting your observations:

- Sharpens your eye for detail

- Builds your patience

- Strengthens your memory

- Encourages creativity

- Honors geology’s origins

Most of all, it reminds us that the first scientific instrument we ever used was not a tablet or GPS device — it was our own attention, guided by the quiet movement of pen across paper.

Closing Thoughts

Writing like a geologist is not simply about using a fountain pen.

It’s about the way we see, notice, and interpret the world.

It’s a small ritual of slowness in a fast-paced world, a bridge between the discipline’s past and our creative present. And for me, every inked line feels like a way of keeping that tradition alive. Below are some of the journals to read about how writing with pens enhance learning and cognitive function.

References:

Mueller, P. A., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014).

The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note taking. Psychological Science, 25(6), 1159–1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614524581

Van der Weel, F. R., & Van der Meer, A. L. H. (2024).

Handwriting but not typewriting leads to widespread brain connectivity: A high-density EEG study with implications for the classroom. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1332834. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1332834

Ihara, A., Nakajima, K., Kake, A., Osugi, S., & Naruse, Y. (2021).

Advantage of handwriting over typing on learning words: Evidence from an N400 event-related potential index. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 15, 679191. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2021.679191

Askvik, E., Van der Weel, F. R., & Van der Meer, A. L. H. (2020).

The importance of cursive handwriting over typewriting for learning in the classroom: A high-density EEG study of 12-year-old children and young adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1810. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01810

Discover more from The Fabulous Scientist

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

absolutely love this, i love art too and panting is one of my favourite outlets. this was a joy to read! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Scientist Soup for dropping by and leaving a kind comment. ❤

LikeLike

I’m glad you enjoyed reading this one! ❤

LikeLike