Grass Padrique | The Fabulous Scientist

In the lab, we obsess over our equipment. We calibrate our equipments, we make sure the connection between computer and equipment is uninterrupted, and we panic if one part acts up. Yet, when it comes to the tool we use to actually process the information inside our heads, most of us settle for a distracted laptop or a cheap, chewed-up ballpoint.

I’ve spent years reading dense technical papers—the kind with equations that sprawl across two columns—and I’ve found that the best way to actually remember what I’m reading is to step back in time. I use a fountain pen.

It’s not because I’m trying to be fancy. It’s because, scientifically speaking, it works better.

The Problem with Typing (The “Human Tape Recorder” Effect)

We’ve all been there. You’re sitting in a seminar or reading a PDF, and you’re typing away at 80 words per minute. You look at your screen and you have a perfect transcript. But if someone asked you five minutes later to explain the mechanism you just typed out, you’d draw a blank.

There’s a reason for that. When you type fast, your brain goes into “autopilot” mode. You are transcribing, not thinking.

Two researchers, Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014), actually tested this. They took a bunch of students and gave half of them laptops and the other half pen and paper. They found that the laptop users took way more notes, but they didn’t learn as much. The people writing by hand couldn’t write fast enough to get every word down. They were forced to listen, digest the complicated idea, and then summarize it in their own words.

That split-second of “digest and summarize” is where the learning happens. In our line of work, we don’t need to memorize the words; we need to understand the logic.

Why a Fountain Pen? (Physics and Friction)

Okay, so writing by hand is better. But why a fountain pen? Why not a ten-cent stick pen?

It comes down to friction and fatigue.

1. Saving your hand muscles A ballpoint pen works on paste ink. To get that thick paste onto the paper, you have to press down hard to roll the ball. If you are trying to summarize a 20-page paper on thermodynamics, your hand is going to cramp up by page four. A fountain pen is a controlled leak. It works on capillary action. The liquid ink touches the paper and flows. You don’t press down; you just guide it. I can write for three hours with a fountain pen and feel zero strain. A colleague new to fountain pen rabbit hole once told me she wrote pages of thoughts using her brand new fountain pen and did not feel any strain at all! You simply can’t do that with a cheap ballpoint pen.

2. The tactile feedback loop There is also something happening with your senses. Mangen and Velay (2010) looked into how touching things affects how we read and write. When you use a fountain pen, you feel the “feedback” of the nib on the paper. You hear the scratch. You see the wet ink drying. This might sound vague, but that sensory input helps “anchor” the memory in your brain. It slows you down just enough to keep you focused. It turns note-taking from a chore into a ritual.

My Protocol for Reading Papers

Here is how I actually do this when I have a stack of papers to get through:

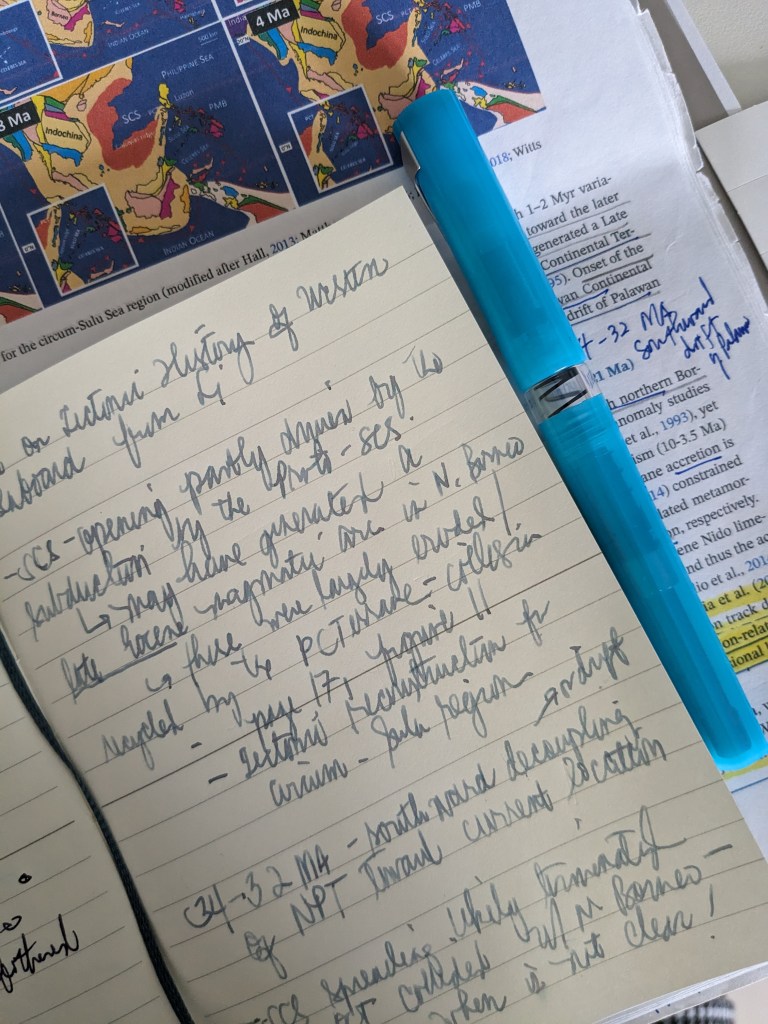

- Print it out. I know, save the trees. But you can’t scroll and scribble effectively at the same time. And note, I only print scientific papers that actually caught my attention while reading it on my Kindle or iPad. If it’s too interesting (and riveting) I need to print it and have to use my fountain pens to highlight certain sections and write down important points.

- The “Margin Attack.” I use the fountain pen to make quick marks in the margins. A question mark for “I don’t believe this data,” or an arrow connecting two different paragraphs. The ink flows fast, so I don’t lose my reading rhythm.

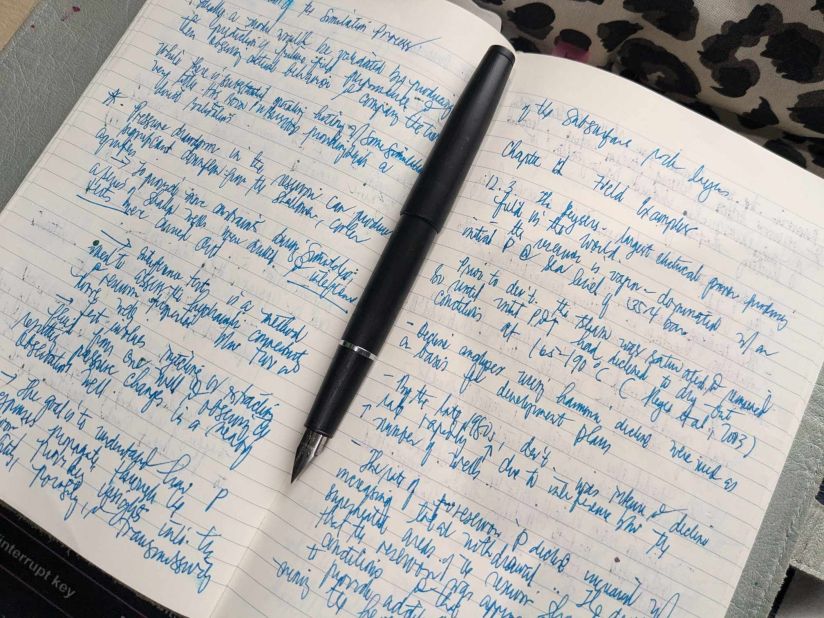

- The Translation. At the end of a section, I stop. I grab my notebook and write a summary. I force myself to translate the academic jargon into plain English. If I can’t explain the concept simply in my notebook, I haven’t really learned it. This is one reason why I still buy notebooks and have a stack of them filled with notes at home.

- Draw it. Keyboards are terrible at shapes. Pens are great at them. If the paper describes a complex structure or a geological fold, I sketch it. If you’ve been on my website a while, you know sketching is something I do almost every day!

The Bottom Line

We spend our careers trying to reduce noise and find the signal. A laptop is an infinite noise machine. A piece of paper and a good pen are silent. They force you to slow down and actually grapple with the data. It’s a simple tool, but sometimes the simplest tools are the most precise.

References

Mangen, A., & Velay, J. L. (2010). Digitizing literacy: Reflections on the haptics of writing. Advances in Haptics, 1(1), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.5772/8710

Mueller, P. A., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note-taking. Psychological Science, 25(6), 1159–1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614524581

Discover more from The Fabulous Scientist

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Wow ❗️

LikeLike